When Dinosaurs Were Reptiles

I am often asked why and when I became interested in illustrating and researching dinosaurs. That’s easy to answer – I was a kid. My interest in prehistoric life goes back as far as I can remember, as does my then primitive efforts at drawing. Where this came from is not apparent. My parents were into entrepreneurial business and Goldwater/Nixonian Republicanism with a passing interest in science. Nor do my other relatives have a scientific background or orientation with one exception described below. But both gene pools were bright, and my folks never discouraged my budding interests. My father has always and justifiably claimed that his sales job at R. P. Andrews paper company abetted my tendency to apply pencil to parchment, he provided endless supplies of the stuff. My late mother saved much of my labors. Dinosaurs are to be found among the ships (many sinking), airplanes (some crashing), great whales (occasionally being attacked by killer whales) and other assorted crude sketches.

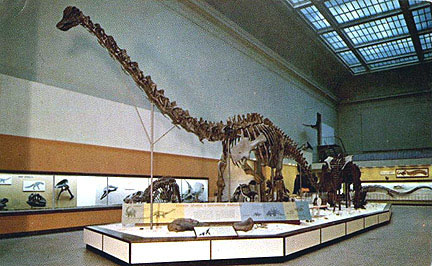

There was many a visit to the Smithsonian’s Museum of Natural History; I grew up in the Northern Virginia suburbs. I dimly recall when the old marine life hall upstairs was still a Victorian style collection with items in glass topped table cabinets with label cards next to them, under an old fashioned, straight bodied whale model and similarly rigid skeleton. When a large pit was excavated for a wing of the museum at the beginning of the sixties I was sure they were digging for dinosaurs. It seems naive, but much of the area happens to be underlain by elements of the middle Cretaceous Potomac group that has produced a number of dinosaur specimens at construction sites in D.C. and Maryland, including a large collection of juvenile sauropods in the suburbs from an 1800s quarry.

There was many a visit to the Smithsonian’s Museum of Natural History; I grew up in the Northern Virginia suburbs. I dimly recall when the old marine life hall upstairs was still a Victorian style collection with items in glass topped table cabinets with label cards next to them, under an old fashioned, straight bodied whale model and similarly rigid skeleton. When a large pit was excavated for a wing of the museum at the beginning of the sixties I was sure they were digging for dinosaurs. It seems naive, but much of the area happens to be underlain by elements of the middle Cretaceous Potomac group that has produced a number of dinosaur specimens at construction sites in D.C. and Maryland, including a large collection of juvenile sauropods in the suburbs from an 1800s quarry.

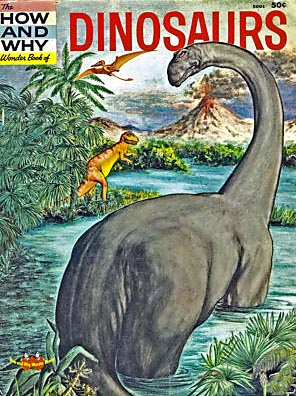

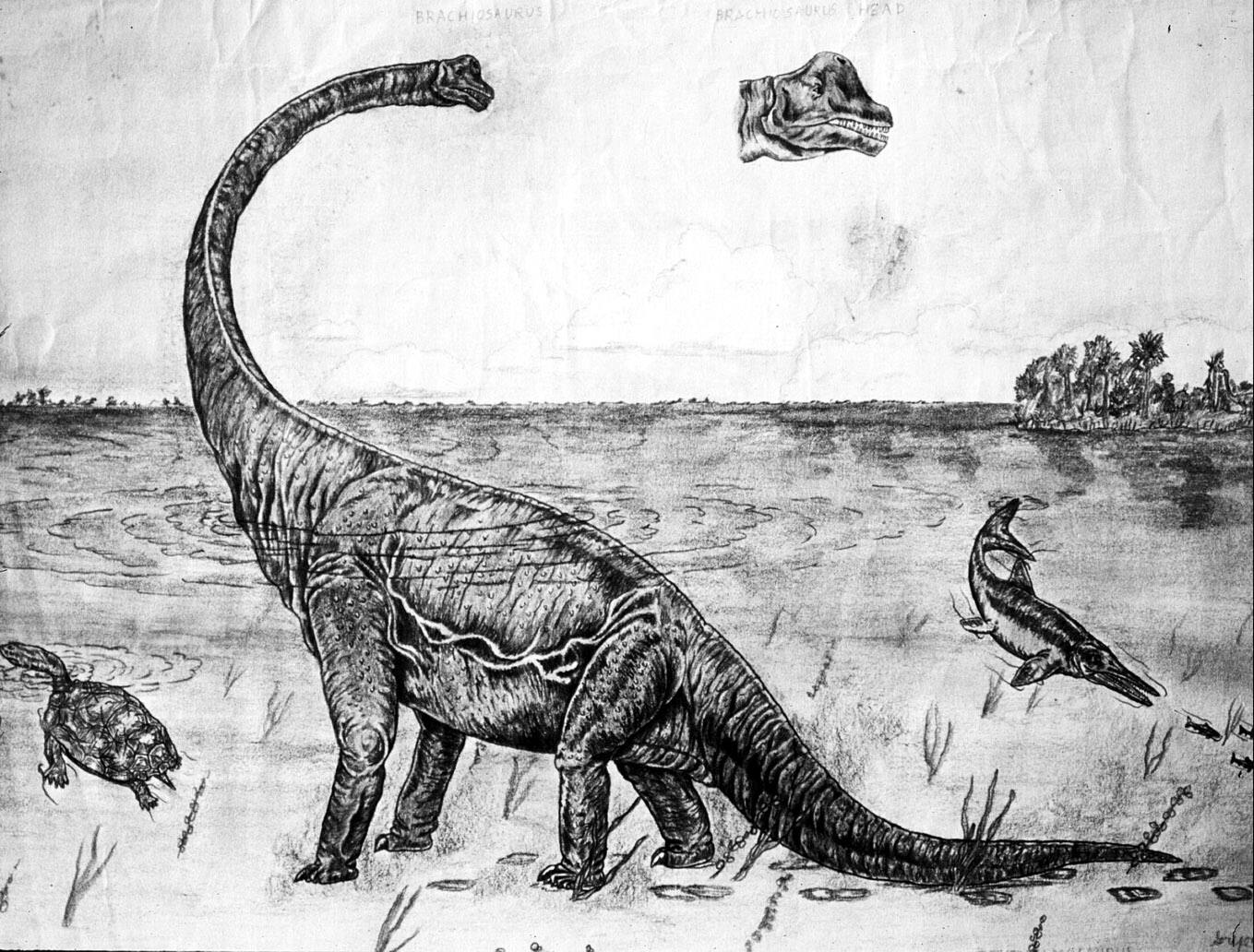

Then there were the books. Many of which I still have, or have tracked down if I then accessed them from school and public libraries. Still remember getting the marvelous How and Why Wonder Book of Dinosaurs at the drug store. It was, however inaccurate. It claimed that Brachiosaurus was the largest dinosaur. Anyone with any sense knew that Brontosaurus was the biggest. (I was opinionated even then.) The large format Giant Golden Book Dinosaurs and Other Prehistoric Reptiles illustrated in colorful detail by Rudolph Zallinger arrived one Christmas. Its illustrations of men digging up dinosaurs in the wild west inspired dreams of hunting dinosaurs. I wore my way through Life’s small format Prehistoric Animals: Dinosaurs and Other Reptiles and Mammals centered on Zallinger’s Yale murals (or at least the preliminary studies).

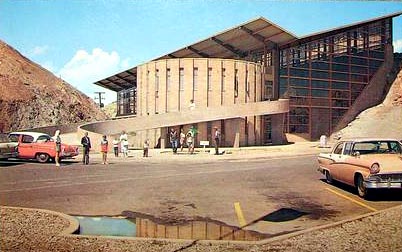

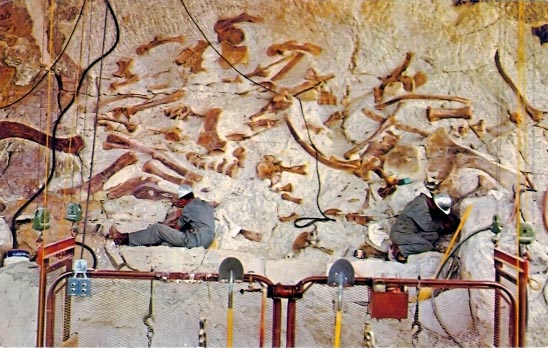

In 1962 my nuclear family of four piled into the Ford Falcon station wagon my Dad had just fitted with the new fangled seatbelts. We headed west to visit relations in Utah. On the way we stopped at Dinosaur National Monument. It proved a disappointment, as too few dinosaur bones had been exposed on the great rock wall of the then new facility. The little museum in Vernal with its cast of Diplodocus in the yard was more appealing. In Salt Lake I met my great aunt Laurel Dewey. A classic grand woman of considerable girth, she was a naturalist and artist who encouraged my fascination with prehistory. After my return to the east she sent me A Little Golden Book: Dinosaurs and the Classics Illustrated comic The Illustrated Story of Prehistoric Animals that fed my interests (these volumes and those in the prior paragraph all appeared in the 1959-61 period).

In 1962 my nuclear family of four piled into the Ford Falcon station wagon my Dad had just fitted with the new fangled seatbelts. We headed west to visit relations in Utah. On the way we stopped at Dinosaur National Monument. It proved a disappointment, as too few dinosaur bones had been exposed on the great rock wall of the then new facility. The little museum in Vernal with its cast of Diplodocus in the yard was more appealing. In Salt Lake I met my great aunt Laurel Dewey. A classic grand woman of considerable girth, she was a naturalist and artist who encouraged my fascination with prehistory. After my return to the east she sent me A Little Golden Book: Dinosaurs and the Classics Illustrated comic The Illustrated Story of Prehistoric Animals that fed my interests (these volumes and those in the prior paragraph all appeared in the 1959-61 period).

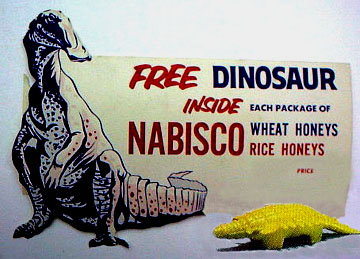

It was something like age 8 that I learned that paleontology has its bitter side. Out of some food product box, cereal probably, I got a little model dinosaur, an ankylosaur. This was when dinosaur toys were uncommon. Understandably I wanted another one. In accord with the designs of the corporate planners, I pestered my mother to purchase another box of the product. She was not at all happy, and warned me that I would probably get the same model. I knew that would not happen - what were the odds - and I kept insisting. Happily pulling out the model from the new box I was infuriated to find the same damn ankylosaur. Things only got worse that rainy day in Arlington. I was so angry that my mother did not let me watch The Three Stooges before dinner.

It was something like age 8 that I learned that paleontology has its bitter side. Out of some food product box, cereal probably, I got a little model dinosaur, an ankylosaur. This was when dinosaur toys were uncommon. Understandably I wanted another one. In accord with the designs of the corporate planners, I pestered my mother to purchase another box of the product. She was not at all happy, and warned me that I would probably get the same model. I knew that would not happen - what were the odds - and I kept insisting. Happily pulling out the model from the new box I was infuriated to find the same damn ankylosaur. Things only got worse that rainy day in Arlington. I was so angry that my mother did not let me watch The Three Stooges before dinner.

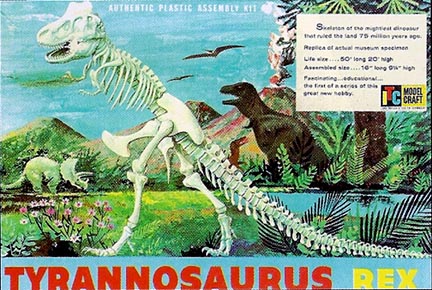

More satisfying was the Marx Prehistoric Times playset, the one with the plump Zallingerian Tyrannosaurus, which I probably got for the holidays. Another gift was the classic ITC Tyrannosaurus plastic model kit, a reasonably accurate replica of the American Museum skeleton in the old tail dragging pose. I decided to get rid of the annoying number tags attached to the assorted parts. When Dad saw what I had done he was aghast. I managed to get it together anyhow.

More satisfying was the Marx Prehistoric Times playset, the one with the plump Zallingerian Tyrannosaurus, which I probably got for the holidays. Another gift was the classic ITC Tyrannosaurus plastic model kit, a reasonably accurate replica of the American Museum skeleton in the old tail dragging pose. I decided to get rid of the annoying number tags attached to the assorted parts. When Dad saw what I had done he was aghast. I managed to get it together anyhow.

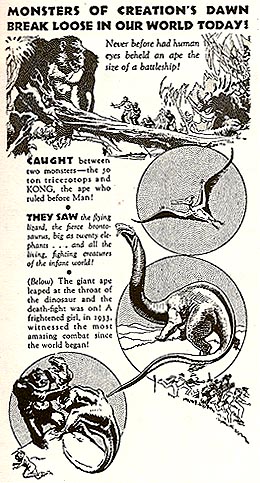

Although not a particular devotee of monster movies, they played their role in my budding dinosaur interest. Especially the classic 1933 RKO King Kong with Fay Wray screaming her way through her adventures with the super ape and their encounters with various sundry dinosaurs and pterosaurs animated by Willis O’Brien. First caught that on my grandparents' telly, around '60 or '61. On the same television I saw the peculiar Nippon flick Rodan. What were those miniature humans about, or were they from another film? And as was often the case I spent the next few days churning out pterodactyloid drawings inspired by the film. The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms scared the willies out of me, especially the scene in which the pseudoarchosaur picks up the dedicated but not particularly bright cop by his head.

And there was that nifty oversized chicken/terror bird in Mysterious Island. Otherwise cannot say I am a particular aficionado of Ray Harryhausen, his work had minimal impact on mine and I did not see many of his films until an adult. Many other dinosaur flicks were a disappointment. Godzilla was obviously a man in a dino-suit. In some pictures (i.e. One Million B.C., Irwin Allen's remade The Lost World) the dinosaurs were nothing more than lizards or baby crocs adorned with makeup appliances to make them look exotic, and slowed down to make them look big (although the lizards made up as Dimetrodons in Journey to the Center of the Earth looked cool.) More serious was the Czech-produced children’s adventure film Journey to the Beginning of Time, which featured a boat trip down a river into the ancient past, its banks populated by an array of ancient creatures largely based on Zdenek Burian's images. It was carried as a serial on the local weekday Ranger Hal show.

And there was that nifty oversized chicken/terror bird in Mysterious Island. Otherwise cannot say I am a particular aficionado of Ray Harryhausen, his work had minimal impact on mine and I did not see many of his films until an adult. Many other dinosaur flicks were a disappointment. Godzilla was obviously a man in a dino-suit. In some pictures (i.e. One Million B.C., Irwin Allen's remade The Lost World) the dinosaurs were nothing more than lizards or baby crocs adorned with makeup appliances to make them look exotic, and slowed down to make them look big (although the lizards made up as Dimetrodons in Journey to the Center of the Earth looked cool.) More serious was the Czech-produced children’s adventure film Journey to the Beginning of Time, which featured a boat trip down a river into the ancient past, its banks populated by an array of ancient creatures largely based on Zdenek Burian's images. It was carried as a serial on the local weekday Ranger Hal show.

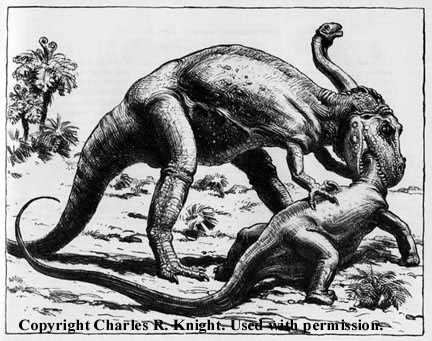

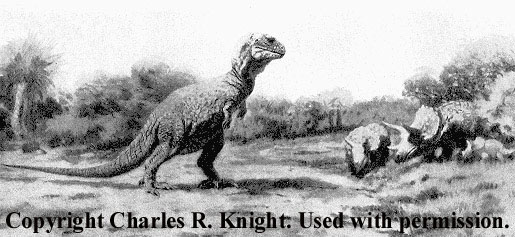

As I entered my preteens and early teens more adult-oriented publications and art garnered my attention. Although Charles Knight died the year before yours truly was born, his atmospheric work still dominated the dinosaur scene, and was my primary influence. When my father was given a set of National Geographics I discovered Knight’s 1942 article on prehistoric life (which noted the exciting research showing that the tails of sauropods arced gracefully down from their hips to the ground, rather than drooping almost straight down from the hips; I was correspondingly delighted to be invited by Scientific American to do an article on his career in the nineties). I found Knight much preferable to Zdenek Burian’s efforts on artistic and other grounds (although he did a very nice study of a Centrosaurus with erect forelimbs). Also important was the trio of works produced by William Scheele; Prehistoric Animals which included dinosaurs, The Age of Mammals, and Prehistoric Man and the Primates (with racist elements standard at the time). They were graced with artistically exquisite charcoal sketches, and an evocative scene of a tyrannosaur assaulting a beached plesiosaur as the frontispiece of the first volume. Also featured were the first fossil skeletons with white bones set in a solid black profile of the body (a style first used by Knight for extant animals in his Animal Drawing: Anatomy and Action for Artists). Almost forgotten is a book I that made an impression on me, John Ostrom’s pre-Deinonychus The Strange World of Dinosaurs featuring (which I now see are derivative) B&Ws by Joseph Sibal.

As I entered my preteens and early teens more adult-oriented publications and art garnered my attention. Although Charles Knight died the year before yours truly was born, his atmospheric work still dominated the dinosaur scene, and was my primary influence. When my father was given a set of National Geographics I discovered Knight’s 1942 article on prehistoric life (which noted the exciting research showing that the tails of sauropods arced gracefully down from their hips to the ground, rather than drooping almost straight down from the hips; I was correspondingly delighted to be invited by Scientific American to do an article on his career in the nineties). I found Knight much preferable to Zdenek Burian’s efforts on artistic and other grounds (although he did a very nice study of a Centrosaurus with erect forelimbs). Also important was the trio of works produced by William Scheele; Prehistoric Animals which included dinosaurs, The Age of Mammals, and Prehistoric Man and the Primates (with racist elements standard at the time). They were graced with artistically exquisite charcoal sketches, and an evocative scene of a tyrannosaur assaulting a beached plesiosaur as the frontispiece of the first volume. Also featured were the first fossil skeletons with white bones set in a solid black profile of the body (a style first used by Knight for extant animals in his Animal Drawing: Anatomy and Action for Artists). Almost forgotten is a book I that made an impression on me, John Ostrom’s pre-Deinonychus The Strange World of Dinosaurs featuring (which I now see are derivative) B&Ws by Joseph Sibal.

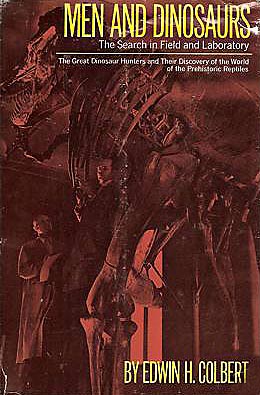

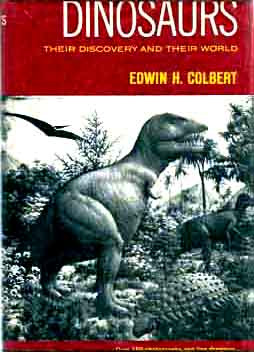

The American Museum of Natural History’s Ned Colbert was the big dinosaur man of the time – ironic in that he was a fossil mammal expert drafted to curate dinosaurs after the loss of the great Henry Osborn. Grew up on his classic Dinosaurs: Their Discovery and Their World, as well as The Dinosaur Book, Dinosaurs, The Age of Reptiles and Men and Dinosaurs. These introduced me to the skillful B&W art of Erwin Christman and John Germann (I also liked an atmospheric painting featuring Allosaurus by virtually unknown American Museum artist George Geselschap circulating in those years). Also enjoyable was Sprague and de Camp’s The Day of the Dinosaur; the mini-stories of daily life in the Mesozoic were particularly evocative.

The American Museum of Natural History’s Ned Colbert was the big dinosaur man of the time – ironic in that he was a fossil mammal expert drafted to curate dinosaurs after the loss of the great Henry Osborn. Grew up on his classic Dinosaurs: Their Discovery and Their World, as well as The Dinosaur Book, Dinosaurs, The Age of Reptiles and Men and Dinosaurs. These introduced me to the skillful B&W art of Erwin Christman and John Germann (I also liked an atmospheric painting featuring Allosaurus by virtually unknown American Museum artist George Geselschap circulating in those years). Also enjoyable was Sprague and de Camp’s The Day of the Dinosaur; the mini-stories of daily life in the Mesozoic were particularly evocative.

Things of the Past

Dinosaurs hardly came up at school, for that matter neither did evolution. One time we students had to correct the teacher that Brachiosaurus, and not Tyrannosaurus, was the largest dinosaur. Early in 1964 my mother enrolled me in a private art class I attended once a week after school. Took public school art classes too. But mainly I was self-taught. Copying other artists was my modus operandi for learning technique. I also developed the habit I still possess of upgrading older works. In 1968-69 I spent the summers with my Greek Orthodox relations in Salt Lake City. Summer of '68, a very pretty relation of Laurel and University of Utah student introduced me to the Fenton’s semi-technical The Fossil Book. Apparently I went supplied with a lot of that R. P. Andrews paper because I turned out a set of images largely derivative of the book’s dinosaurs. The next summer I did none. This was a pattern I followed in those years, bursts of artistic activity followed by months of neglect as I tended to other interests. Upon returning to the pencils I repeatedly found that my skill level had automatically jumped to a new level as my brain rewired with ontogeny.

Dinosaurs hardly came up at school, for that matter neither did evolution. One time we students had to correct the teacher that Brachiosaurus, and not Tyrannosaurus, was the largest dinosaur. Early in 1964 my mother enrolled me in a private art class I attended once a week after school. Took public school art classes too. But mainly I was self-taught. Copying other artists was my modus operandi for learning technique. I also developed the habit I still possess of upgrading older works. In 1968-69 I spent the summers with my Greek Orthodox relations in Salt Lake City. Summer of '68, a very pretty relation of Laurel and University of Utah student introduced me to the Fenton’s semi-technical The Fossil Book. Apparently I went supplied with a lot of that R. P. Andrews paper because I turned out a set of images largely derivative of the book’s dinosaurs. The next summer I did none. This was a pattern I followed in those years, bursts of artistic activity followed by months of neglect as I tended to other interests. Upon returning to the pencils I repeatedly found that my skill level had automatically jumped to a new level as my brain rewired with ontogeny.

In 1968 I met a year- or two-younger female relation from the Mormon side of my mother’s family. She became an admirer of the more mature me to my benign amusement. Waxed enthusiastic over my dinosaur pictures - until we were in the basement of her Salt Lake home before the big summer afternoon party. Somehow the fact that I believed humans descended from apes came up but I thought nothing of it. Her eyes grew wide at the horrible concept. Her parents had told her otherwise (heretical by Christian norms, Mormon doctrine denies Biblical inerrancy and accepts an ancient Earth as well as the evolution of animals, but it presumes that all humans descended from Adam and Eve, who were the creation of our planet’s God, who in turn is an exalted human).

Backing away, she carefully avoided the evil me the rest of the day! Most amusing and yet sad. Next summer, I think, Laurel drove me and my cousin Bill to Dinosaur National Monument. Nothing like the drive up the Green River towards the quarry and Split Mountain. The display was much more satisfying this time around, with a diverse array of skeletons by then exposed on the cliff wall.

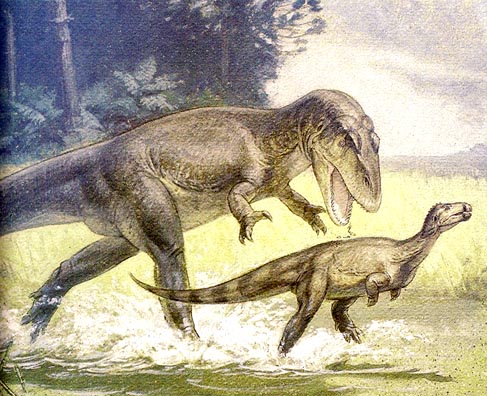

Making even more of an impression were the superb little color dinosaur studies by Alaskan wildlife artist Bill Berry, as they were vastly superior to Zallinger's and Burian's, and even edged out Knight. My favorite was the evocative scene of snorkeling Diplodocus heads, followed closely by the tail in the air Allosaurus chasing Camptosaurus into the water which is as modern as anything seen today. Now in storage, I was pleased to include a rare presentation of Berry’s body of work in The Scientific American Book of Dinosaurs which I edited. Also on display was another and very different set of paleoart, the wonderfully odd, often garish, and incredibly prolific production of local paleontologist and artist Ernest Untermann. Produced in the WWII era, his dinosaur and other prehistoric scenes were often as eccentric as the former seaman and old socialist himself.

Making even more of an impression were the superb little color dinosaur studies by Alaskan wildlife artist Bill Berry, as they were vastly superior to Zallinger's and Burian's, and even edged out Knight. My favorite was the evocative scene of snorkeling Diplodocus heads, followed closely by the tail in the air Allosaurus chasing Camptosaurus into the water which is as modern as anything seen today. Now in storage, I was pleased to include a rare presentation of Berry’s body of work in The Scientific American Book of Dinosaurs which I edited. Also on display was another and very different set of paleoart, the wonderfully odd, often garish, and incredibly prolific production of local paleontologist and artist Ernest Untermann. Produced in the WWII era, his dinosaur and other prehistoric scenes were often as eccentric as the former seaman and old socialist himself.

In intermediate school I constructed a crude sculpture or two (which my mother proudly displayed to visitors), and I used the arc tailed Diplodocus in my only science fair project (8th grade). It was about how enormous sauropods had to live buoyed by water, where their high set nostrils allowed them to breath while lurking in the colossal rivers that meandered across the Amazon-like Morrison habitat of the Jurassic. The judges seemed impressed, but it did not win (I was not disappointed, the winner had a superior project). In later high school, the underwater photographs in a National Geographic article on the hippos of the crystalline Mzima Springs inspired me to illustrate an Apatosaurus in a similar mode. By then my art was becoming original in nature.

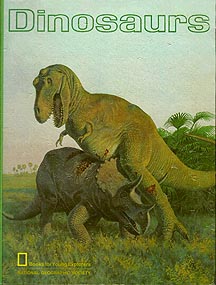

In the 1960s the Smithsonian began to feature the superbly artistic and detailed Cenozoic murals by renowned wildlife artist and meticulous mammal anatomist Jay Matternes, and they remain among my favorite paleoart. At the end of the decade National Geographic released a nifty little book by the renowned paleoanthropologist Louis Leakey, Animals of East Africa, that included some excellent examples of Matternes restorations. Early in the next decade NatGeo sent out flyers for a series of kids books, including one on dinosaurs to be illustrated by Matternes. The promotional material included a delightful color study of a resting ornithomimid. When the book arrived it was somewhat disappointing. Most of the images in the flyer were not included and those that were looked rushed. Matternes did not really have a handle on dinosaurs. The NatGeo book was one of the last gasps of the old school of dinosaur art. So was Willy Ley’s Worlds of the Past which covered a number of prehistoric habitats. Illustrated by Zallinger, I liked its atmospherics.

In the 1960s the Smithsonian began to feature the superbly artistic and detailed Cenozoic murals by renowned wildlife artist and meticulous mammal anatomist Jay Matternes, and they remain among my favorite paleoart. At the end of the decade National Geographic released a nifty little book by the renowned paleoanthropologist Louis Leakey, Animals of East Africa, that included some excellent examples of Matternes restorations. Early in the next decade NatGeo sent out flyers for a series of kids books, including one on dinosaurs to be illustrated by Matternes. The promotional material included a delightful color study of a resting ornithomimid. When the book arrived it was somewhat disappointing. Most of the images in the flyer were not included and those that were looked rushed. Matternes did not really have a handle on dinosaurs. The NatGeo book was one of the last gasps of the old school of dinosaur art. So was Willy Ley’s Worlds of the Past which covered a number of prehistoric habitats. Illustrated by Zallinger, I liked its atmospherics.

Do not think my thoughts in those days was just dinosaurs 24/7. Being big on aircraft especially of the military kind, I considered a career in aeronautics. Also rocketry. Then a big space program and SciFi fan, Werner von Braun and Arthur C. Clarke were my heroes. Clarke whom I would have some e-mail contact with remained so, but not Braun as I came to understand the Nazi/SS background of Hitler’s amoral rocketeer. Toyed with writing science fiction for awhile. Also mulled becoming a commercial artist, or of doing modern wildlife. My interests in matters non-paleo continues in multiple expressions.

I can no longer recall how it came about, but I got a shot at having an illustration published on the cover of the Weekender section of The Evening Star in 1972. Visited the art editor at their headquarters where a couple of rookie reporters were beginning to delve into that Watergate thing. A Smithsonian theme was decided upon. I sketched the full size model of Stegosaurus in the dinosaur hall, and the stuffed African elephant in the lobby. Not to my surprise they chose the artistically superior pachyderm.

One thing that did not exert a major influence were dinosaur documentaries. At a time when just three networks dominated the airwaves, public broadcasting was still no-budget educational TV, and dinosaur paleontology was something of a backwater, there simply were none. In the late '60s I was all aflutter when it was announced that a National Geographic special on reptiles would begin with new stop-motion animation of dinosaurs. When the program aired – back in those primitive times you actually had to be sure to watch the program when it was broadcast as there being no way of recording it – the typical sprawling dinosaurs were something of a let down, and the product never aired elsewhere.

Getting information in the pre-digital era was often difficult. Not until I came across a small and already obsolete illustration of Brachiosaurus in Colbert’s Men and Dinosaurs did I see a direct side view of the skeleton of a dinosaur discovered before the Great War. Dinosaurs have always enjoyed a level of popularity since their discovery in the early 1800s. The Flintstones (which I loved) was a successful primetime sitcom. Sinclair Oil adopted a dinosaur as their logo (it still adorns their gas stations out west) and commissioned dinosaur restorations I fondly recall. Yet most dinosaur discoveries of the time were not considered particularly newsworthy. The major exception were the announcements by "Dinosaur" Jim Jensen of his colossal new Morrison sauropods, as when he appeared on either To the Tell Truth. But scientifically speaking, not all that much seemed to be going on in the 1960s. What was going on was not percolating up to the public, hence I was not aware that the science of dinosaurs et al. was beginning to shift with John Ostrom’s work on the bird-like Deinonychus, and Bakker’s speculations in Yale’s Discover on dinosaurs as bird and mammal analogues. Nor did I know about Nick Hotton’s delightful little 1963 Dinosaurs, which portrayed dinosaurs as a more athletic form of reptile than thought for the time. After all, the beasts were just extinct reptiles doomed by their tiny brains to certain extinction.

The dinosaur world I grew up in was classical. They were universally seen as scaley herps that inhabited the immobile continents. There was no hint that birds were their direct descendents. Being reptiles, dinosaurs were cold-blooded and rather sluggish except perhaps for the smaller more bird-like examples. They all dragged their tails. Forelimbs were often sprawling. Leg muscles were slender in the reptilian manner. Intellectual capacity was minimal, as were social activity and parenting; the Knight painting of a Triceratops pair watching over a baby threatened by the Tyrant King was a notable exception. Hadrosaurs and especially sauropods were dinosaurian hippos, the latter perhaps too titanic to even emerge on land, and if they did so were limited by their bulk to lifting one foot of the ground at a time. Suitable only for the lush, warm and sunny tropical climate that enveloped the world from pole to pole before the Cenozoic, a cooling climate and new mountain chains did the obsolete archosaurs in, leaving only the crocodilians. Dinosaurs and the bat-winged pterosaurs were merely an evolutionary interlude, a period of geo-biological stasis before things got really interesting with the rise of the energetic and quick witted birds and especially mammals, leading with inexorable progress to the apex of natural selection: Man.

It was pretty much all wrong. Deep down I sensed something was not quite right. Illustrating dinosaurs I found them to be much more reminiscent of birds and mammals than of the reptiles they were supposed to be. I was primed for a new view. (Next)